Excerpt two recounts Purzycki’s nightmarish first day on the job as Delaware State’s head football coach. (Excerpt one, ICYMI, is right here.)

The previous evening he had his final interview and while he knew he had done well, he also thought the school was going to hire another candidate. He was stunned when Townsend called and offered him the job. As he made his way back to Dover the next morning for a press conference Purzycki was unaware that upon hearing the news students had reacted negatively and protests had been staged. More protests were planned after Purzycki’s press conference. In any discussion of worst first days ever on a new job, Purzycki’s experience would rank near the top. The excerpt is edited (and adjusted for clarity) from three chapters in the book.

About 10 hours after he was offered the head coaching position at Delaware State College, Purzycki made his triumphant return to Dover for the news conference. He hadn’t slept well, but he wasn’t tired. His fitful sleep was due mainly to the excitement that washed over his mind.

He’d faced the media often as a high school head coach and he’d dealt with reporters as a player and a coach at Delaware, but this morning would be his first formal news conference. Far from intimidating him, the idea of a roomful of reporters waiting to hear his vision for building a successful program at Delaware State thrilled him.

He walked into Townsend’s office a few minutes after 8:00 a.m. and felt his excitement fade as Townsend greeted him with a concerned look.

“Joe, I have to talk to you before we go over to the press conference,” he said gravely. “We had some problems here on campus last night.”

“What are you talking about?” Purzycki responded.

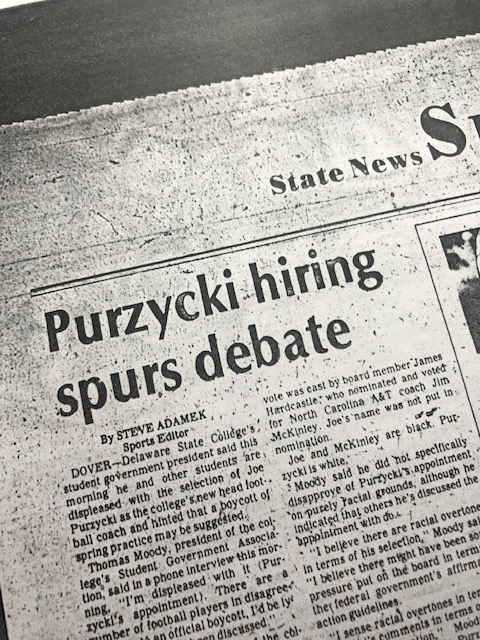

From the Wilmington News Journal

“Young kids, reacting the way they sometimes do,” Townsend said, searching for the right words. “Well, they kind of overdid it in the dorms. They were upset about the decision to hire you and there was a lot of anger.”

The explosive reaction to Purzycki’s hiring was the result of building tension on campus going back to the firing of (previous coach) Charles Henderson in December. Most of the players realized a coaching change was necessary, but when word got out that the school was going to invest money in the program with a new weight room, a training table, and possibly a locker room, some players were upset. They knew Henderson had asked for many of those things but never got them and that struck them as unfair.

“All of a sudden, the school was going to ante up all this money for things they could have and should have done after we went 7-and-3 in 1978,” said defensive lineman Calvin Mason. “Why didn’t they give the other coaches the tools they needed?”

Then came Scott Wasser’s column predicting a white coach, which had not only complicated Townsend’s efforts to hire Purzycki but created a lot of discussion within the team. (Wasser was a columnist for the Delaware State News and had written a story the week before suggesting that Purzycki was the best guy for the job and should be hired.)

“The story about how you’ve got to hire a white coach didn’t help things at all,” said Mason’s defensive line teammate Anthony Sharpe. “No one wanted to be told what to do and the thinking was we should get a black coach. A lot of people didn’t want to change their ways.”

“Most of the players were interested in bringing in a coach who was notable in the black college football space,” said wide receiver Walt Samuels. “There were several heated meetings and the overriding choice of the football community and the student community was Billy Joe. He was a veteran coach and my sentiment was that he would be a better fit for us.”

That opinion was the popular one among players, students, and faculty at the school. How could the school not hire Billy Joe? He checked every box the football community thought the Hornets needed in a new coach, and by the board of trustees’ final interviews everyone (including Purzycki) figured Joe had the job in the bag.

The Eagles assistant himself must have felt that way as he walked over to the players’ dorm to introduce himself following his interview. His hiring certainly seemed to be a fait accompli.

“Billy Joe came in and talked to us,” said Samuels. “He had that pro background and he was with the Eagles and they’re going to the Super Bowl. He was going to bring a pro-style offense in and we were all excited. We all thought it was a lock that he had gotten the job.”

While Joe visited the players, other students milled around the library awaiting official word of his hiring. Shortly after 9 p.m., the door to the trustees’ meeting room opened and chairman William Dix cleared his throat to make the announcement.

“The new head football coach at Delaware State College is,” Dix began before pausing as people in the library leaned forward in anticipation, “Joe … Purzycki.” The way Dix paused as he made the announcement, combined with the fact that most people in the room thought Billy Joe was a shoo-in for the job, led to a moment of stunned silence as people realized what had happened. The guy they wanted for the job, the guy with NFL credentials and college football head coaching experience who had come to Dover from the Super Bowl just for the interview was not going to be hired.

The job instead went to the Delaware assistant. Purzycki. A guy who had no connection to the NFL, who had only been a head coach in high school, and whose only way into the Super Bowl on Sunday was if he bought a ticket.

And … he was white.

Reaction to the announcement was swift, unanimous, and loud. Students and student-athletes alike felt it was clear Billy Joe was the better and more experienced candidate and that the only possible explanation for Purzycki’s hiring was that school officials had buckled under the pressure of Wasser’s column.

After calling Purzycki to inform him that he had the job, Nelson hurried across campus to the player’s dormitory to tell Joe. But bad news, using its normal rate of speed, beat him there. When he walked into the dorm to find Joe the mood was already ugly.

“It was almost like a riot when they announced they were going to hire Coach Purzycki,” said offensive lineman Calvin Stephens. “The students and the team all wanted Billy Joe and it was really tense in the dorm.”

Tight end Terry Staples had just completed his freshman season and remembers negative reaction among some teammates based on the perceived social injustice. “A lot of players were upset. They were saying, ‘How are they going to bring a white coach to a black college? We should be trying to keep black coaches employed and working.’”

Mike Colbert was a freshman hoping to walk on to the football team in 1981. “Billy Joe was a decorated NFL player who was on the staff of the Eagles, they’re getting ready to go to the Super Bowl, and we find out they’re gonna hire a high school coach? It was devastating.”

By the time Townsend found him, Billy Joe had already heard the news. Delaware State Student Government Association president Thomas B. Moody had come directly from the library when word got out that Purzycki was the choice.

“He was disappointed when he found out he didn’t get the job,” Samuels remembered, “and when everyone saw how disappointed he was, we got disappointed. That’s what caused the uproar.”

“A lot of people thought the school had let us down,” said quarterback Sam Warren. “People had become disturbed with the athletic department.”

Townsend knew the players wanted Joe and he knew the players would be upset. But he was surprised at the level of anger. “I thought they would be shocked, not hostile,” he said. As Townsend left the dorm he was the target of a pointed barb from an unknown player.

“You sold us out, Townsend! You gave it to the white people!”

That accusation had the desired effect. It stung. But Townsend knew it was pointless to engage in debate with an angry crowd, so he moved on. He also knew where he had come from. He had faced hatred, bigotry, and double-standards in his life. No one needed to lecture him about how the world worked. He believed in hiring the right person for the job no matter his skin color. And that’s what he had done.

Now, he faced a big challenge: dealing with a student body and football team that was categorically not on board with the decision to hire Purzycki, while at the same time convincing Purzycki that everything was going to be fine. As he had done during the protracted search and interview process, Townsend tried to downplay to Purzycki the events of the previous night.

“They’re students,” he said. “They’ll get over it.”

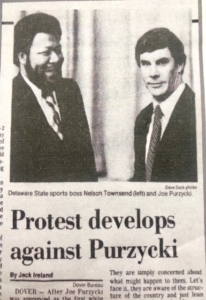

Townsend and Purzycki walked over to the news conference together, and both were struck at how quiet it was on campus. It was decidedly less quiet in the auditorium, which was packed with students along with the reporters.

Purzycki sat at his seat at a rectangular table in the center of the room and felt his heartbeat quicken as he picked up on the confrontational vibe in the room and realized that maybe not everyone was ready to “get over it.”

Dr. Mishoe and Townsend each spoke for a few minutes about how excited they were to have Purzycki at Delaware State. They listed his accomplishments, talked about the good times ahead for the program and then opened the floor for questions for their new coach.

But the first question was more of a statement:

“The players and the students all wanted Billy Joe to be the head coach. Students protested your hiring last night and plan to hold similar protests today. What’s your reaction to that?”

The bluntness caught Purzycki off guard, but he recovered quickly. He heard himself say something about just wanting to be a football coach and to build something successful at DSC.

“Do you realize that there are a group of players who are organizing a boycott and are threatening not to play for you?”

“Mr. Townsend shared with me that some of the students were unhappy about the decision,” he said. “Here’s the way I’m approaching this situation: I understand there’s never been a white coach at an HBCU and I understand the sensitivity of the students here to that situation. But I have one job and that’s to produce a first-class football program. That’s what I’m going to do.”

“There’s a rumor among the students and the players that you’re going to turn us into the University of Delaware and recruit primarily white players for the team. Is that true?”

Purzycki admitted that he would borrow from Delaware’s system and attempt to duplicate their success in Dover but that there was no plan to exclusively recruit white players.

“You’re being given many benefits like a weight room, a larger staff of full-time assistants, and a locker room that were all denied to the previous coach, who was black. Do you think that is fair?”

On it went. He had prepared himself for questions about race but had not anticipated the succession of barbs and questions regarding protests and petitions, with football seemingly on the periphery.

He called the Portland State game “a terrible injustice” and promised to “get things going and get things turned around. And when we do that everyone is going to know who we are.”

A reporter brought things back around to the color of Purzycki’s skin and the campus-wide disapproval of his hiring.

“I don’t think the race issue will be a problem for me, whatsoever,” he said. “It may be with some people, but I hope I can overcome that quickly. I’m a football coach and I’d like to put everything else aside. My program is going to have consistency, fairness, and integrity throughout.”

Eventually, people were done asking questions. The new coach of the Hornets was a little shaken at what he had just gone through, but he felt he had handled things OK and he got excited again as he and Townsend made their way to the day’s next appointment: his first official meeting with his team.

This is a moment Purzycki had thought about for several weeks. His desire to be a leader of young men was his primary reason for taking the job and he couldn’t wait to stand in front of a group of players and share with them his vision for how they were going to become successful at Delaware State. He entered the meeting room a few minutes early, spread his notes on the lectern, and thought about what he wanted to say.

Only five players showed up.

Purzycki nervously checked his watch and continually glimpsed the doorway. He eventually realized that no one else was coming. He made a few comments and thanked the players who were there.

The paltry attendance at the meeting sent a clear message that the new coach’s most monumental task would be to win over his own team.

“A lot of players were still shocked,” said Terry Staples. “They were like, ‘Oh, no. Not a white coach here. Nope, nope, nope, nope.’”

“There were a lot of guys in the dorm saying, ‘I’m not going to that meeting because he’s not going to be MY head coach,” said Mike Colbert.

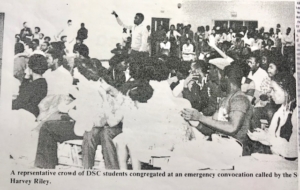

A photo from the Del State student paper shows students meeting to protest Purzycki’s hiring.

“The temperament among many players was that they weren’t going to play for a white coach at an HBCU. It was very real. There were petitions going around and there were several players who were very adamant that they were not going to play for Purzycki. All of that was driven in a large part by the culture of the school, and the HBCU community.”

Townsend suggested they get Purzycki settled into his new office. As they made their way across campus, they couldn’t help but notice hundreds of students streaming to what was referred to in the Hornet, the student newspaper at Delaware State, as an “emergency convocation to discuss the issue of whether new head football coach Joe Purzycki was, in fact, the best qualified for the job.”

The student paper left no doubt as to what they thought about Purzycki’s qualifications, derisively nicknaming him “The Polish Prince.”

“Someone told us that there were already 400 kids at the student center who were staging a sit-in protest,” Purzycki said. “Players and students were going to speak at the protest. There were placards on the walls of buildings and we saw several students carrying protest signs.”

The scene in the student center was passionate bordering on chaos.

“I remember Mr. Hamilton (Allen Hamilton was a Del State alum, the head of the school’s math department, and was on the search committee for the new coach) trying to calm everyone down,” Walt Samuels said. Both times Hamilton tried to speak and explain the decision, he was shouted down by angry students.

“I had to go in front of the students and explain why we hired him,” Hamilton said. They literally booed me off the stage. Players wouldn’t talk to me.”

According to a story in the Hornet, there was discussion among students in between speeches that Purzycki’s hiring was obviously the first step in bringing more white athletes and more white students to Dover thus eroding DSC’s HBCU culture.

“All of us are talking about the fact of having a white coach,” a student yelled. “But what will we do about it?”

Meanwhile, Townsend and Purzycki made their way into the athletic offices. When he reached his new office at the end of the hallway, Purzycki looked around. Any hope that his day was going to turn around evaporated.

“It was a very small office,” he said. “There was an empty anteroom in front of it. There was a green chalkboard with a giant hole in the middle that someone had tried to repair with plaster. There was a filing cabinet with several drill holes in one side. It looked like someone had lost the keys at one point and then used a drill on it, so they could get in.”

Purzycki sat down at his desk and took it all in. He realized it was cold in the room and looked for a thermostat to adjust the heat. It was then that he noticed one of the windows was broken leaving the room open to the icy January breeze. The wastebasket was full. An ashtray spilled over. Purzycki looked at his desk phone and sighed.

“The receiver was hanging from the phone by the wires and athletic tape. It was caked with a yellow substance that looked like dried eggs. It was filthy.”

He picked the phone up and was shocked to find out that it worked. His first official act as head coach at Delaware State was to use that phone to call the phone company to order a new phone. Purzycki hung up and sat at the desk. At Delaware, even the defensive backs coach had a first-rate office. Now, as he sat in his overcoat in a room with no heat, looking at a phone held together by athletic tape, a broken file cabinet, and a chalkboard with a hole in it, and as he considered everything else he had been through, Purzycki had a chilling thought.

“Tubby was right,” he said to himself. “What have I done? I left Camelot for this?” (Tubby Raymond was Purzycki’s coach at Delaware and advised him against taking the job.)

Purzycki left the office and found Townsend. He had a few routine HR documents to fill out and he needed Townsend to show him where he had to go to get that done.

As they walked Purzycki’s mind raced: “I was so exhausted. I didn’t expect 400 protestors. I didn’t expect the players not to show up for the meeting. I didn’t expect the office to look as pathetic and rundown as it was. I never expected the tidal wave that I walked into. I felt sick to my stomach. It was the loneliest day of my life. I began to think this might be a huge mistake in judgment on my part.”

Finally, he stopped walking and turned to face his new boss. “Nelson, I just don’t know if this is going to work.”

Townsend looked at Purzycki in silence. He knew the day hadn’t unfolded in any way Purzycki could have possibly envisioned. But he liked how he had handled the news conference and he thought DSC had the right man for the job. So, he was taken aback to hear Purzycki gathering the white flag.

“I told you that you were going to have to be tough and that this wasn’t going to be easy,” Townsend said his voice rising in anger. “We’re not having a bunch of 18 and 19-year-olds tell us what to do. This is going to pass, Joe. We have bigger things to do here.”

Townsend’s anger had a clarifying effect on Purzycki who suddenly realized the full extent of what his new boss had put himself through to give him the chance he’d wanted. Townsend had been getting hit from all sides since Wasser’s column had been published.

For two weeks the AD had been confronted by students, players, faculty, staff, and alumni, all wanting to know just what in the hell he was thinking promoting a white man as the new head coach at Del State (and a white man from Delaware, to boot). Townsend was irritated with the tone of the questions at the news conference and he was furious that so many members of the team elected to skip the first meeting with their new head coach. He was angry, but he was not going to allow Purzycki to even consider walking away now.

“We have bigger things to do here,” he repeated. “I don’t want to hear anything about this again.”

Purzycki knew, from that moment, he was not alone. He and Townsend were in the fight together.

“If Nelson had shown even the slightest bit of hesitancy,” Purzycki recalled years later, “if he had given any indication that he agreed with me that it might not work, I would have driven home and asked Tubby for my job back at Delaware.

“Instead, I knew I had his full support and I wasn’t going to back out because he needed me as much as I needed him. Quitting at that point would have been the wrong thing to do. He was dependent on me and I knew he was in my corner.”

Click here to see a video about the book.